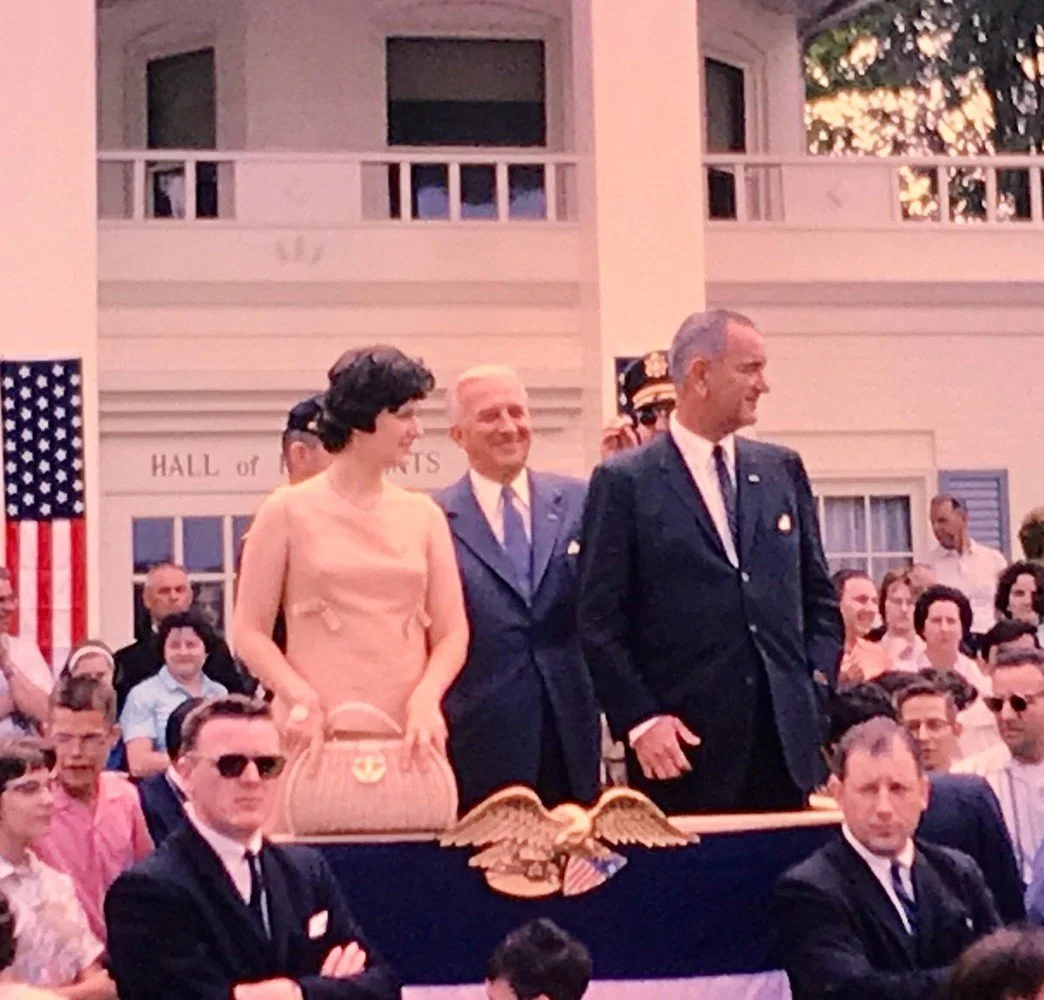

Profiles in Character: Lyndon Johnson Turns Compassion into Action for Forgotten Americans

“No event in which I will participate in St. Augustine will be segregated,” Vice-President Lyndon Johnson wrote in early 1963 to Fannie Fullerwood, president of the local branch of the NAACP. The venue selected at the start of the city’s celebration of its four hundredth anniversary was “whites only.” He made sure blacks were seated at that banquet. That spring, he spoke at the press club for African American journalists in Washington, D.C. - an invitation never previously accepted by a President, Vice-President or Cabinet official. On May 30th, he spoke at the Gettysburg National Cemetery, a century after Lincoln. “The Negro asks justice,” he said. “We do not honor him – we do not honor those who lie beneath this soil – when we reply by asking “Patience.”

In that spring of police dogs and fire hoses in Birmingham, Alabama and a rising national consciousness about segregation, Johnson’s actions might not seem particularly noteworthy. As chronicled in Robert Caro’s biography (The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Passage of Power) most Southern politicians weren’t concerned about what Johnson was saying. He was, they thought, still the man who for two decades in Congress had voted against all but two civil rights bills – and those (1957, 1960) he’d dramatically weakened before passage. Many Southerners accepted those laws as a way to make Johnson more acceptable to Northern liberals, hoping he could then gain the presidency and secure segregation for years to come.

There was another man inside that politician. Lyndon Johnson had tasted poverty deeply in his youth. His father died penniless, the family counted on dinners provided by friends and Lyndon picked cotton and worked on a road gang. He tasted exclusion too – from taunting, being outside the schools “in crowd” and from better universities he couldn’t afford. He had taught poor Mexican-American children in a segregated school in Cotulla, Texas. As a legislator who learned that a Mexican-American war hero was denied burial in a Texas “whites-only” cemetery, he said “By God, we’ll bury him in Arlington!” Johnson railed at the indignity suffered by his African-American cook who when driving to his Texas ranch had to pee on the side of the road because she was barred from motels and service stations.

His gestures in early 1963, however, represented the most he could do about racism and poverty in the traditionally powerless post of Vice-President. Thrust by Kennedy’s assassination into the presidency, power and passion were then united. Kennedy had sent a tough Civil Rights bill to Congress, where it languished at the hands of powerful Southerners. Johnson, unlike Kennedy, was a master of the legislative process. Advised to weaken the bill if he wanted anything passed, he refused. “Well, what the hell’s the presidency for,” he shot back. Speeches were not enough. “[I]t is the politician’s task to pass legislation, not to sit around saying principled things,” he said.

In a Joint Session on November 27th, Johnson put Congress on notice:

“no memorial or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy’s memory than the earliest possible passage of the civil rights bill for which he fought so long. We have talked enough in this country about equal rights. We have talked for one hundred years or more. It is time to write the next chapter, and to write it in the books of law.”

In his State of the Union Address on January 8th, he continued:

“Unfortunately, many Americans live on the outskirts of hope – some because of their poverty, and some because of their color, and all too many because of both. Our task is to help replace their despair with opportunity.”

Johnson, astute to the character and interests of key members of Congress and reminding them of their moral obligations, got the bill to the floor of both chambers. It would take months, but the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed into law on July 2nd.

He was not done. He shepherded into law the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Civil Rights Act of 1968, Medicare, Medicaid, Head Start and the Fair Housing Act of 1968. He nominated Thurgood Marshall as the first black on the Supreme Court and Robert Weaver as the first black Cabinet member (Housing and Urban Development). He took particular pride in the Higher Education Act of 1965, returning to San Marcos, Texas where he went to the “poor man’s” college:

“I shall never forget the faces of the boys and the girls in that little Welhausen Mexican School, and I remember even yet the pain of realizing and knowing then that college was closed to practically every one of those children because they were too poor. And I think it was then that I made up my mind that this nation could never rest while the door to knowledge remained closed to any American.”

Lyndon Johnson’s presidency is tarnished for many Americans by his prosecution of the Vietnam War, and his character certainly had flaws. Yet his imperfections should not make us miss his achievements for people or color, the poor and the elderly – and because of those gains for all Americans.

Photo Credit: Oscar White

(If you do not currently subscribe to thinkanew.org and wish to receive future ad-free posts, send an email with the word SUBSCRIBE to responsibleleadr@gmail.com)