Profiles in Character: Barbara Johns Leads a Civil Rights Fight for a Better School

In the fall of 1950, 15-year-old Barbara Johns, the oldest of her five siblings in their Farmville, Virginia home, was helping them get ready for school. After they left, she left too. Realizing she forgot her lunch pail, she went back inside to get it and thus missed her school bus. An hour passed during which she tried to hitch a ride to school. She then saw a half-full school bus of white students pass by on their way to the all-white high school.”Right then and there,” she later wrote, “I decided that indeed something had to be done about this inequality.”

The inequality was staggering. Moton High School, her segregated all-Black school, had about 450 students, more than twice its planned capacity. The overcrowding was “managed” by adding tar-paper shacks. When it rained, water came through the roof, forcing some students to use umbrellas in class. When it was cold outside, only those students near the wood stove could get warm. The school had no cafeteria, no science labs and no gym. Parents complained but to no avail despite the 1896 Supreme Court Plessy v. Ferguson ruling that legalized segregated schools if the provided “separate but equal” education.

Encouraged by a music teacher she confided in and who asked her “why don’t you do something about it?” she met with some students to decide on a course of action. They agreed to launch a student strike, which they began on April 23, 1951. They got the principal to leave school by the ruse of a phone call telling him two students were about to be arrested at the local bus station. When he left, Johns forged a note from him to teachers saying they should send all their students to a special assembly, to which the teachers were then told to leave. As soon as they did, Barbara rose to speak. Her sister Joan recalled that “All the students, like me, were in shock.” Barbara explained the reasons and plan for the strike and asked the students to join it. They all marched out of school and headed for the county courthouse to speak to the School Superintendent and make their case for improving the school. When he refused their pleas, students picketed both inside and outside the school for the rest of the day. “We want a new school or none at all” read one sign. Barbara also spoke to the broader black community at a mass meeting to build support for the strike.

The student strike continued for two weeks, ending only when students were assured that legal action was underway. Barbara had called the NAACP office in Richmond to ask for help. “She wanted us to take her case,” recalled Oliver Hill, a lawyer there, “She was insistent.” On April 25th, lawyers from the NAACP arrived in Farmville and agreed to help, but only if the legal case was for integrated schools not just a better facility at Moton. On May 23rd the Dorothy E. Davis, et al. versus County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia was filed with the lead plaintiff a 14-year-old student. Dismissed by the U.S. District court, the case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court where it was combined with four other cases in what would, in 1954, lead to the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision overturning the separate but equal doctrine.

Barbara was harassed for leading the school strike and the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross in front of her home. Afraid for her, her parents sent her off to Montgomery, Alabama to live with her uncle, Vernon Johns, who was himself an early pioneer for black civil rights and had helped educate the Johns children about Black history when he visited their home.

After graduation, Barbara Johns would enter college but leave to marry William Powell, Jr., move to Philadelphia, raise five children and become a school librarian in the city schools. She completed a degree at Drexel University in 1979 but her vocal activism in the civil rights movement had ended with the effort at Moton.

In her time protests for Black civil rights were rare and efforts were led only by adults. The Montgomery Bus boycott was still four years in the future. Barbara Johns’s student-led protest was thus a forerunner of the power of student activism that would later erupt in full force in the student lunch-counter sit-ins and the “Children’s Crusade” in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963 when several thousand children would be arrested and police dogs and fire hoses released to attack them.

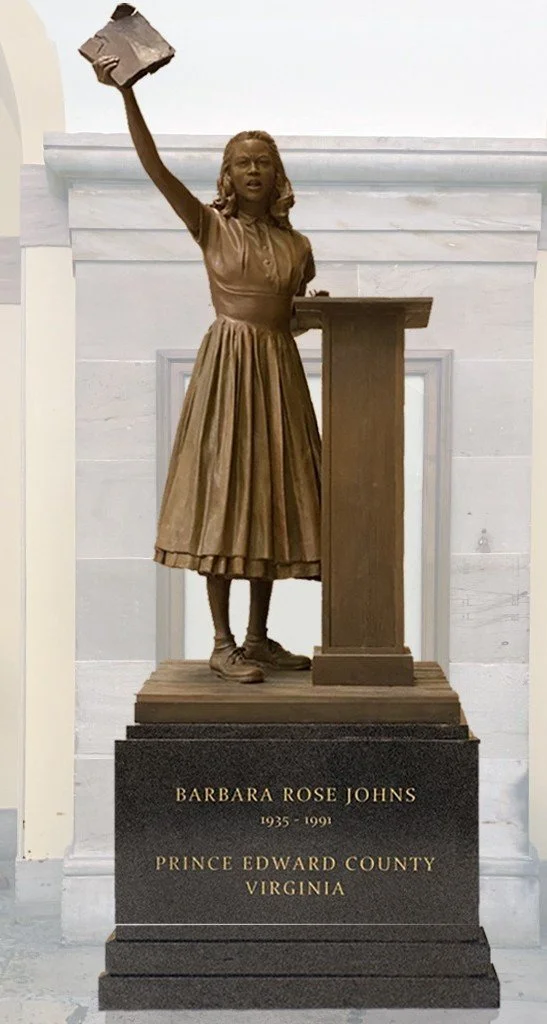

The story of Barbara Johns was recently memorialized on December 16, 2025 with the unveiling of her statue in the U.S. Capitol. After the statue of Robert E. Lee was removed in 2020, the State of Virginia selected her to be featured as one of only two every state is allowed to place in Statuary Hall. Two quotes on sides of the pedestal capture her achievement. One is from Isaiah: “and a little child shall lead them.” The other is from her: “Are we going to just accept these conditions? Or are we going to do something about it?”

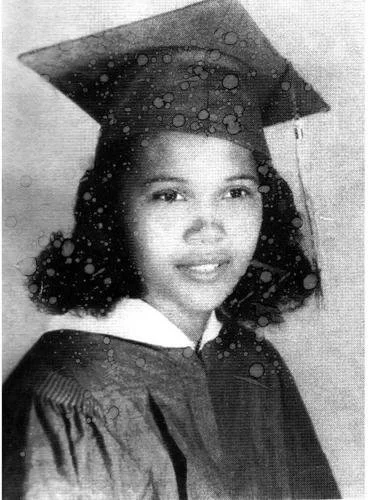

Photo Credit: wikipedia.com (1952 graduation photo of Barbara Johns)

(If you do not currently subscribe to thinkanew.org and wish to receive future ad-free posts, send an email with the word SUBSCRIBE to responsibleleadr@gmail.com)