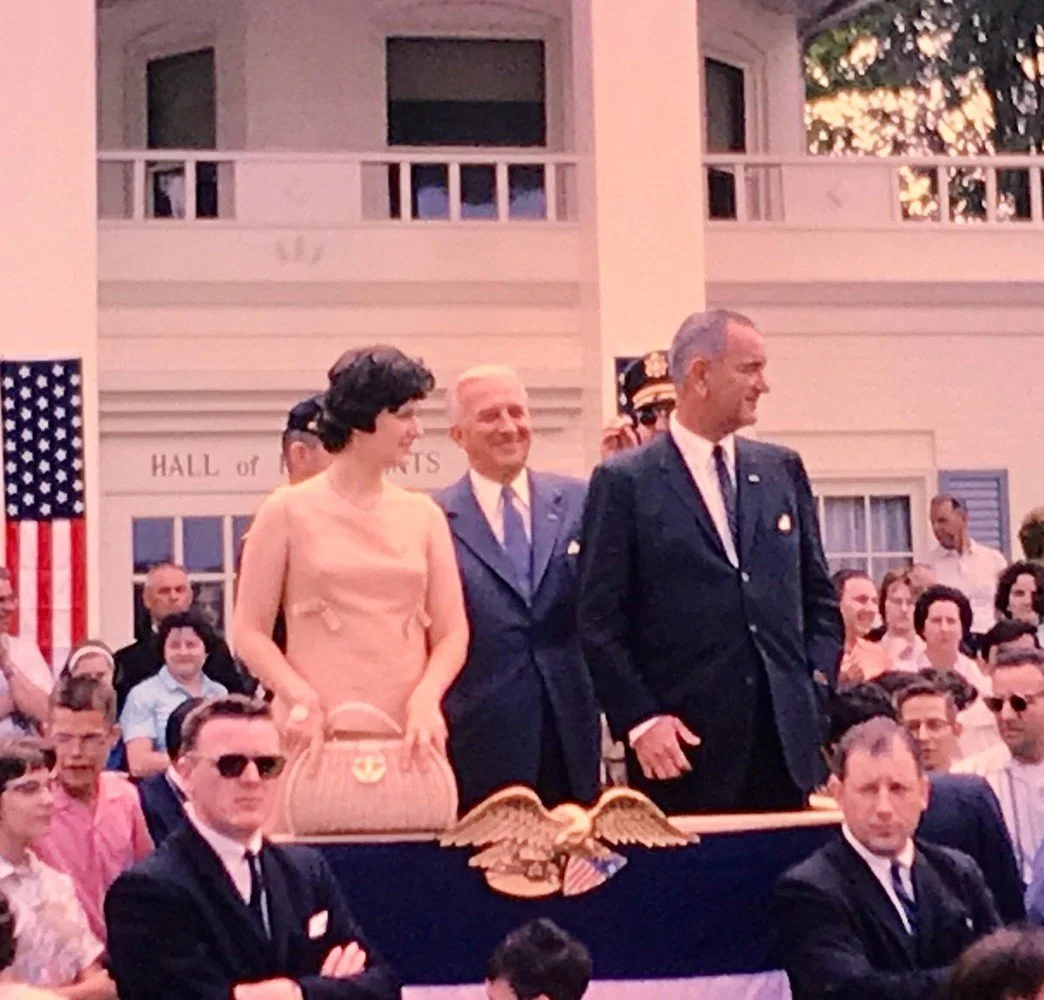

Democracy’s Documents: Vice-President Lyndon Baines Johnson Focuses on Civil Rights at Gettysburg, May 30, 1963

Lyndon Johnson had been a staunch opponent of civil rights legislation throughout his political career. John F. Kennedy picked Johnson as his running mate in 1960 to gain support among Southern Democrats who feared the liberal Kennedy. It would take police dogs and fire hoses attacking children in Birmingham in early May 1963 to push Kennedy to act. On June 11 he would announce he was sending a civil rights bill to Congress. Before that, on the hundredth anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg on May 30th, Johnson made a statement of his own.

He began by recalling that long ago battle for freedom:

“On this hallowed ground, heroic deeds were performed and eloquent words were spoken a century ago.

We, the living, have not forgotten--and the world will never forget--the deeds or the words of Gettysburg. We honor them now as we join on this Memorial Day of 1963 in a prayer for permanent peace of the world and fulfillment of our hopes for universal freedom and justice . . . Until the world knows no aggressors, until the arms of tyranny have been laid down, until freedom has risen up in every land, we shall maintain our vigil to make sure our sons who died on foreign fields shall not have died in vain. ”

Calling for Americans to “maintain the vigil of peace,” Johnson pivoted to his central message:

“we must remember that justice is a vigil, too - - a vigil we must keep in our own streets and schools and among the lives of all our people--so that those who died here on their native soil shall not have died in vain.

One hundred years ago, the slave was freed.

One hundred years later, the Negro remains in bondage to the color of his skin.

The Negro today asks justice.”

In his Letter from Birmingham Jail, Martin Luther King, Jr. would include a searing indictment of segregation when he explained “why we can’t wait” to those who counseled patience. Whether Johnson had seen a version of the Letter, he understood its message:

“We do not answer him--we do not answer those who lie beneath this soil--when we reply to the Negro by asking, "Patience."

It is empty to plead that the solution to the dilemmas of the present rests on the hands of the clock. The solution is in our hands. Unless we are willing to yield up our destiny of greatness among the civilizations of history, Americans--white and Negro together--must be about the business of resolving the challenge which confronts us now.

Our nation found its soul in honor on these fields of Gettysburg one hundred years ago. We must not lose that soul in dishonor now on the fields of hate.

To ask for patience from the Negro is to ask him to give more of what he has already given enough. But to fail to ask of him--and of all Americans--perseverance within the processes of a free and responsible society would be to fail to ask what the national interest requires of all its citizens.”

The end of segregation, Johnson said, must come through the proper use of law:

“The law cannot save those who deny it but neither can the law serve any who do not use it. The history of injustice and inequality is a history of disuse of the law. Law has not failed--and is not failing. We as a nation have failed ourselves by not trusting the law and by not using the law to gain sooner the ends of justice which law alone serves.

If the white over-estimates what he has done for the Negro without the law, the Negro may under-estimate what he is doing and can do for himself with the law.”

The law, Johnson understood, will not always move swiftly:

“If it is empty to ask Negro or white for patience, it is not empty--it is merely honest--to ask perseverance. Men may build barricades--and others may hurl themselves against those barricades--but what would happen at the barricades would yield no answers. The answers will only be wrought by our perseverance together. It is deceit to promise more as it would be cowardice to demand less.”

Concluding his remarks, Johnson tied the achievement of racial justice to the cause of American freedom:

“In this hour, it is not our respective races which are at stake--it is our nation. Let those who care for their country come forward, North and South, white and Negro, to lead the way through this moment of challenge and decision.

The Negro says, "Now." Others say, "Never." The voice of responsible Americans--the voice of those who died here and the great man who spoke here--their voices say, "Together." There is no other way.

Until justice is blind to color, until education is unaware of race, until opportunity is unconcerned with the color of men's skins, emancipation will be a proclamation but not a fact. To the extent that the proclamation of emancipation is not fulfilled in fact, to that extent we shall have fallen short of assuring freedom to the free.”

As president after Kennedy’s tragic death, Johnson would work with Congress to pass the Civil Rights Law of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Photo Credit: Johnson at Gettysburg, courtesy of the Gettysburg Museum of History